This vision is reflected in the second plank of HEAL’s Platform For Real Food: Opportunity for All Producers. Explore the plank using this toolkit - learn about the historical context that guides our work, our solutions, what HEAL members are doing to realize our collective goals, the resources that guide us and how you too can take action towards building a food system that creates pathways for small and independent farmers and fishers, especially those from BIPOC communities.

This vision is reflected in the second plank of HEAL’s Platform For Real Food: Opportunity for All Producers. Explore the plank using this toolkit - learn about the historical context that guides our work, our solutions, what HEAL members are doing to realize our collective goals, the resources that guide us and how you too can take action towards building a food system that creates pathways for small and independent farmers and fishers, especially those from BIPOC communities.

Our Solutions

- Secure and protect land access and non-predatory credit and capital for independent producers, particularly producers of color

- Equalize and expand access to crop insurance, technical assistance, low interest credit, and technical assistance for independent producers, particularly producers of color

- Place moratorium on farm land foreclosures with an independent review on cause and effect, particularly for farmers of color

- Create and implement farmer debt forgiveness programs in cases of discrimination

- Radically increase support for beginning farmers and for the sustainability of independent farmers

- Recognize fisheries and small fishers as part of the food system by supporting research, technical assistance and federal support parallel to that of agriculture producers

- Secure fair markets, fair prices, and fair wages for all farmers and farmworkers to enable economically stable livelihoods (see Planks 1 and 3)

- Support smaller and independent producers to pay a living wage to farmworkers (see Plank 4)

- Fully fund land-grant institutions to work in the public interest and stop private interests from determining agricultural research

- Increase public research dollars for improved, non-GMO seeds, breeds, and farming methods

- Protect the ocean commons from privatization

Explainer

The second plank of HEAL’s Platform for Real Food calls for the creation of a farming system that makes it possible for everyone to grow, raise, catch, hunt and forage for healthful food in ways that are environmentally sustainable and culturally appropriate for themselves and their communities. This includes:

- Independent farmers and ranchers who are Black, Indigenous and People of Color (immigrants and US-born) who operate small to midsize farms and utilize ecological farming and ranching practices, and fair labor practices

- Indigenous land and water stewards who use traditional agricultural practices to grow food for their communities

- Foragers and hunters

- Independent fishers whose practices align with conservation principles

- Farmworkers, a majority of whom are Latinx and Indigenous immigrants, and have been cultivating land for decades,possess a wealth of agricultural knowledge and skill, but have limited access to land and resources

- Urban farmers who grow community gardens in cities, often in abandoned plots, providing food and community in neighborhoods previously lacking in nutritive food sources

- Beginning farmers and fishers, especially those from BIPOC communities, who want to grow their own food and reclaim their relationship with the land

Small-scale farmers and fishers and community producers, especially those from BIPOC communities do more than growing and catching food. Their work directly impacts community health and wellbeing, and because many of them use ecological agricultural practices rooted in traditional farming, their efforts contribute to improving soil health, increasing regional biodiversity, and ultimately mitigating the impacts of the climate crisis. Community farms, cooperative and urban gardens have also historically been spaces where people can gather, and reconnect with the land and their people.

Industrial agriculture is designed around an extractive relationship with the land, water, and other natural resources—large scale monocropping, or the practice of growing the same one or two crops (mostly corn and soy today) on the same plot of land, ultimately depletes soil health, making it less productive over time and increasing farmers’ reliance on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. A lot of these crops go toward animal feed used on factory farms, aka Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs). CAFOs contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, and burden workers and rural communities with polluted air and water. Industrial fisheries have a similar impact on our oceans. Large amounts of pesticides and antibiotics are used in on and offshore aquafarms, and overfishing, bottom trawling, and longline fishing not only impacts fish stock but can harm ocean biodiversity. Emerging developments like genetically modified salmon also pose a threat to native species and undermine indigenous communities’ food sovereignty.

This extractive mode of production is at the root of our food system’s role in the climate crisis. It’s behind the greenhouse gas emissions, air and water pollution, biodiversity loss, and soil depletion that are symptoms of a failing food system.

WATCH: SALMON PEOPLE: The risks of genetically engineered fish for the Pacific Northwest

A remedy to the climate crisis

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), more than 90% of farms around the world are run by an individual or a family and rely primarily on family labor. Despite the myth that industrial agriculture and biotechnology are needed to feed the world, these family farms produce about 80% of the world’s food. Throughout time, people have evolved place-based cultivation techniques and trading systems, adapting to ecological and social conditions. And while industrial agricultural systems rely heavily on fossil fuels and chemical applications that contribute to climate change and biodiversity loss, smaller-scale producers not only depend on thriving ecological systems, they often contribute to them through nutrient cycling, habitat creation, and more.

Several studies have shown that utilizing traditional farming practices, which are rooted in stewardship and the interdependence of environmental and human health, can help mitigate the impacts of the climate crisis. Traditional agroecological practices (also known as regenerative agriculture) are built on a mutual relationship with the land.

Instead of using harmful pesticides, fertilizers, and monoculture practices, the majority of farmers around the world are small-scale producers using compost, cover cropping, minimal tillage, and crop diversity to grow food. In doing so, they are nurturing soil health, protecting biodiversity, and sequestering carbon in the soil, thereby reducing the amount of carbon in our atmosphere. Scientists say that transforming our food system to reflect these practices can potentially change the fate of our planet. Many farmers are already seeing small, but significant results like richer soil, increased biodiversity in the surrounding areas, and improved water retention. Many BIPOC producers who neither benefit from nor have an interest in industrial agricultural practices continue to farm using this traditional ecological knowledge.

EXPLORE: Real Food Media’s Tackling Climate Change Through Food Organizing Toolkit

Building community and resilience

For BIPOC communities, food and farming have long been connected to civil rights, community self-determination, and collective liberation. Many BIPOC agricultural communities have long been at the forefront of creating models that are heralded as part of a new sustainable agricultural movement.

While the predominantly white back-to-the-land “movement” of the 1970s is often credited for food distribution models like Community Supported Agriculture (CSA’s, often known as “the box”), its origins are simultaneously rooted in Japan and birthed in the US via Black communities in the deep South in the 1960s. The original CSAs served as a means for consumers to buy-in and share the risk of crop failures due to weather or other unforeseen circumstances, and to share equally in the harvest.

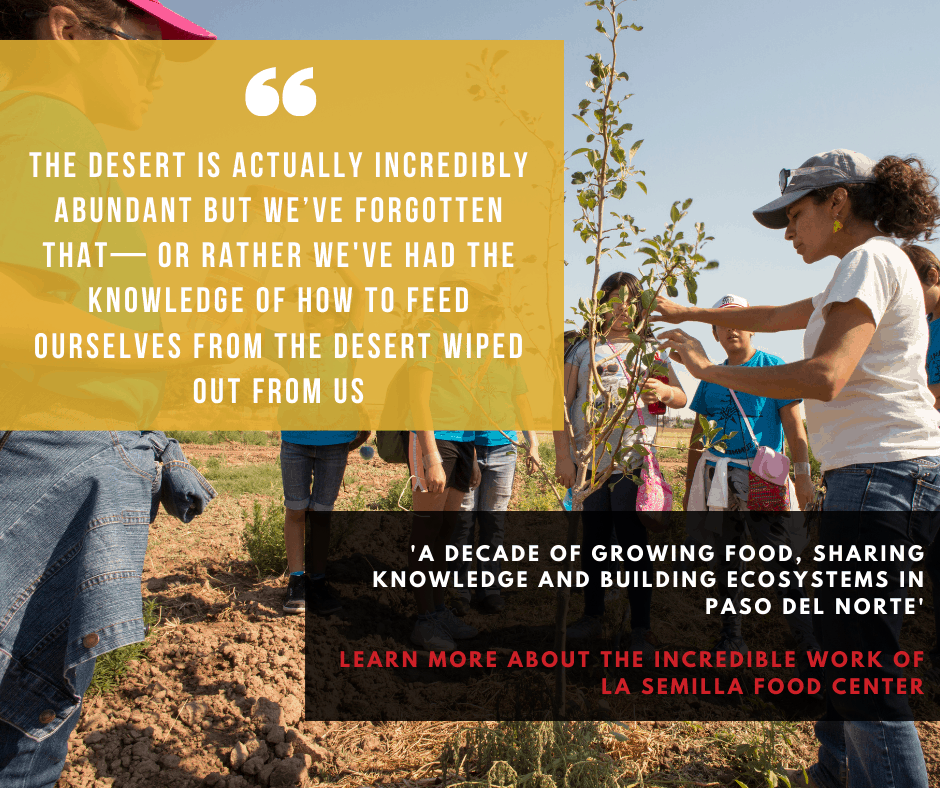

WATCH: Food, race, and justice | Malik Yakini | TEDxMuskegon

Cooperative practices by farmers in the South played a key role in the Civil Rights movement and because Black and Brown communities continue to experience food apartheid to this day, they have always turned to each other and to the community to feed themselves and provide healthful food for their families. Some For many that have been systematically left out of the food system and often borne the brunt of a food system that was designed to amass wealth through their oppression, growing food on their terms and ensuring the communities’ access to it, is in itself a radical political act. The majority of BIPOC producers today are politically motivated by the need to fight for a more equitable, and ecologically sound food system and reclaim their connections to the land that has been historically denied to them. They use their position as providers and their land access to create space for learning, healing and resisting. Organizations like Truly Living Well in Atlanta and La Semilla Food Center in Anthony, NM have succeeded not only in growing food for local communities but also in creating a welcoming space for people to reconnect with their food sources, with each other and learn how to farm. The Dine Food Sovereignty Alliance is working with indigenous producers to honor their ancestral traditions and heal their land and advocate for a return to traditional farming practices and stewardship that their communities have used for generations.

Even as the largest chemical pesticide, fertilizer, and pharmaceutical companies buy up the food system and consolidate power by controlling seeds and inputs, indigenous communities and other BIPOC producers continue to grow, save and trade seeds - and with these traditional heirloom seeds - keep their cultures alive.

WATCH: Rematriation of Seeds | Rowen White

As we take measures to mitigate the climate crisis and commit to fighting systemic racism and white supremacy in our food systems, we should start by acknowledging the stewardship and resilience of these producers and organizations and their contributions to the community, the movement, and the planet. We should be asking ourselves what we can do to ensure that small-and-medium producers, especially those from BIPOC communities need to thrive. Apart from changes in policy and leadership, philanthropic dollars, community patronage and institutional funding can go a long way in honoring the work of BIPOC producers and ensuring that they can continue their critical work.

The current food system is a web of national and global production and supply chains controlled by a handful of large corporations like Walmart, Aldi, Dole Foods, JBS, Flower Food, and Aramark. The ‘success’ of this centralized system is measured by profit derived from extracting from and depleting land, water, and air, exploiting workers, and undermining democratic processes.

The current model of food production and distribution is fuel-intensive and an active contributor to the climate crisis—both in its reliance on chemical pesticides and fertilizers made using fossil fuels, as well as in its fuel-intensive distribution network that has the entire country consuming food from a handful of food hubs. These industrial supply chains have also proven to be rigid and inadequate during crises and natural disasters such as hurricanes, forest fires, and public health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

What seemed to many as a shortage in food supply during the early weeks of the pandemic was in reality, the inability of the centralized distribution channels to respond to disruptions in transportation and the shuttering of usual outlets like cafeterias, restaurants, and stadiums. During this time, communities in some regions had limited or no access to food, while producers in the same regions lacked access to markets. By April 2020, as the rest of the country was attempting to ‘flatten the curve’, meatpacking plants turned into COVID-19 hot spots, putting workers' lives and public health at risk.

Community-based food systems are crisis-proof food systems

Decentralized, smaller-scale, community-based food outlets proved more reliable in the face of the pandemic—direct markets (farmer’s markets, Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs), and Community Supported Fisheries (CSFs)) saw an uptick, while mutual aid groups stepped in to ensure that at-risk community members were taken care of. At the same time, more people were growing their food, with the help of community gardeners and seed keepers. Community-based economies proved critical in this time of crisis, and we know that to survive future crises, especially those brought about by climate change, we have to transform our food system.

REPORT: Reframing Food Hubs- Food Hubs, Racial Equity, and Self-Determination in the South

To do this, we need immediate and long-term investment in localized food systems, Policy that supports the growth of small and medium-sized farms, and institutional adoption of value-based procurement programs like the Good Food Purchasing Program (GFPP) that can help small and mid-sized producers to grow their operations, access markets and nurture mutually beneficial relationships between producers, workers, and consumers. We need shorter supply chains that grow pasture-raised livestock on independent small and medium-scale farms with small and mid-sized meat processors which are also more environmentally sustainable and result in more nutritious food for eaters. We also need increased funding for research on the role of regenerative agriculture and traditional agricultural practices in sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, preserving and nurturing biodiversity, and subsequently mitigating climate change.

Grassroots organizations, small-scale producers, Indigenous communities, and cultural organizers have been building resilient and equitable food systems for years. As the pandemic has revealed, these systems are best positioned to withstand and mitigate crises. Investing in them will move us closer to a food system that can not only carry us through crisis like the pandemic and climate change, but also mitigate their impacts.

In 1997, 400 Black farmers sued the USDA for racial discrimination for about 15 years—and won. In the lawsuit, titled Pigford v Glickman, the court ruled that USDA officials had ignored complaints from Black farmers, and denied them farm aid, loans, and other support based on their race. The USDA admitted that they had delayed Black farmers’ paperwork until planting season was over, and denied them crop disaster payments. The landmark lawsuit and the case were settled for $1 billion in 1999.

That same year, another lawsuit—Keepseagle v Vilsack—made the case that the discrimination was not just towards Black farmers. Since 1981 USDA officials had discriminated against Native farmers and ranchers in loan programs and loan servicing, leading many of them to lose their lands and livelihoods. The case was settled in 2010 and the claimants received compensation, debt relief, and other programmatic relief which totaled to about $800 million. Once news of the Pigford vs Glickman case hit the news, many more black farmers came out to talk about the rampant discrimination they had faced. While farmers relied on loans from the Farm Service Agency to cover operating costs and hold on to their land, this option was rarely, if ever, available to BIPOC farmers.

READ: How USDA distorted data to conceal decades of discrimination against black farmers

WATCH: Catfish Kingdom

‘A system cannot fail those it was never built to protect’

The reality is that from the outset, federal and state agencies, and agriculture policy were not designed to include BIPOC communities. Legislation like the Homestead Act of 1862 which paved the way for farming in the Midwest was crafted with the explicit intent of forcing indigenous people of the land which was then redistributed only to European settlers. Under the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, which forms the basis for today’s Farm Bill, crop subsidies were reserved for landowners (majority white)—sharecroppers and tenants (majority Black) who were excluded subsequently lost their land and livelihood. Labor laws like the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), and the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), also frequently left out farm labor and domestic labor, which were, and still are, overwhelmingly performed by People of Color. A historical lack of BIPOC representation in decision-making bodies has meant that BIPOC producers are still grappling with a system that was never meant to serve them. This explains why farming and agriculture continue to be overwhelmingly white, and federal and state agencies still fail to address the multitude of issues faced by small and medium-sized producers of color.

READ: For Native Americans, Land Is More Than Just the Ground Beneath Their Feet | The Atlantic

For instance, even before BIPOC producers approach a loan agency, a multitude of factors are already working against them.

Most loans are configured for large, high-yielding farms that are owned by white farmers or large corporations but because of a race-based wealth gap resulting from combined systems of oppression—white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism—BIPOC farmers are more likely to operate small to medium-sized farms with lower revenue. A lack of access to intergenerational wealth means that they cannot build strong credit histories, which can further a cycle of financial instability, making them ineligible for future loans. Because of a history of discrimination at financial institutions, they’re also more likely to lack clear titles to the land that they inherited. Similarly, other Farm Bill programs like federal crop insurance, conservation and environmental and research grants (like Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) or Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) and a variety of other incentives and training are geared towards protecting the rights and livelihoods of white farmers, and the bottom lines of large agribusinesses.

Any steps the USDA has taken to address this problem, like carving out funds for “socially disadvantaged farmers & ranchers” throughout its suite of programs have failed to address the generational impacts of exclusionary policy. Furthermore, due to a lack of transparency on the part of agencies like the USDA, it’s often hard to judge how much has changed for BIPOC producers during this time but some reports point to things not having changed to a large extent. An investigation by The Counter revealed that not only is discrimination by the USDA still rampant, but it has also gone to lengths to conceal the impacts of this discrimination and paint a false picture of the revival of Black farming

The work of bridging racial disparities, including advocating for and working towards more BIPOC representation and more democratic forms of leadership in decision making, building new systems of community land stewardship and cooperative models, and holding the USDA accountable to BIPOC producers is now driven by BIPOC-led organizations. For example, at the HEAL School of Political Leadership session in Albany, GA, a Black organic farmer talked about how he was building community and engaging in policy at the federal level by planning farmer fly-ins with other Black farmers in the region. The session was also organized on land that is held and managed by New Communities Inc., one of the country’s first land trusts, started by Shirley and Charles Sherrod. Leaders like Savi Horne of the Land Loss Prevention Project are fighting to ensure that younger Black farmers have titles to, and can keep their families’ land. This organizing work is also taking place on municipal and state levels: In Philadelphia, Soil Generation is in protecting urban gardens from the city and developers, and in doing so, fighting both food apartheid and gentrification. In Richmond, CA, Urban Tilth is partnering with the county to use public land to grow food for their community. Statewide in California, the California Farmer’s Justice Collaborative passed the California Farmer Equity Act which begins to directly address the challenges faced by BIPOC producers. In New Mexico, La Semilla is among the organizations advocating for the Healthy Food Financing Initiative which provides resources that can help producers and small retailers to provide fresh food to low-income urban, and rural communities. On Navajo Nation, Black Mesa Water Coalition and others are cultivating restorative food economies and writing tribal policy for food sovereignty. Nationally, the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance is growing and trading seeds for cultivation.

These local-level policy changes model what could happen on a federal level, where change is harder to achieve because powerful agribusiness lobbies wield considerable power over policymakers. However, folks like Southeastern African American Farmers’ Organic Network (SAAFON), National Black Food and Justice Alliance, Hmong Farmers Association, National Family Farm Coalition, Native Farm Bill Coalition, the Federation of Southern Cooperatives, Black Urban Growers and many more are continuing their work of advocacy, outreach, and research to expand BIPOC producers access to federal and state resources.

EXPLORE: Regaining Our Future - Native Farm Bill Coalition

A legacy of stolen land and stolen labor

The history of agriculture in the US is one of colonization and enslavement, followed by a long history of denying land rights to Black, Indigenous, and People of Color which manifests differently in urban and rural areas. Between 1784 and 1887, 1.5 billion acres of land was stolen from indigenous people—through war and attempts at genocide, outright theft and legislative appropriations like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Homestead Act of 1862 (the total landmass of what is now the United States is 1.9 billion acres). From the vast plains of Iowa to the fertile acres of California’s Central Valley, America’s farms are on land that was taken from the Indigenous communities that once stewarded it.

The violent colonization was an act of physical and cultural genocide; not only were millions of Indigenous people killed, but a majority of them were removed from their homelands, which they had stewarded for thousands of years. As a result, they were disconnected from their traditional foodways and forced to assume European systems of land ownership through legislation such as the Dawes Act. To date, profit-driven corporations and the U.S. government continue to violate treaties and extract oil, water, minerals, and more from lands that even by U.S. law are governed by indigenous communities.

EXPLORE: To learn more about the indigenous lands you currently occupy, explore this map. You can also download an app.

From the early 1600s, enslaved Africans were abducted from their homelands to cultivate cotton, sugarcane, tobacco and more on monoculture plantations on these stolen lands—these were some of the nation’s most valuable exports at the time and served to lay the foundations for American capitalism, and simultaneously set the scene for American agriculture for centuries to come.

Towards the end of the Civil War, in 1865, Union leaders met with a group of Black leaders in Savannah, Ga to discuss how the Union government could support previously enslaved Black people. In 1865, based on what he heard from those leaders, Union General William T. Sherman passed an Order declaring that each family would be given land to farm on—“a plot of 40 acres of tillable ground”. Subsequently, 400,000 acres that were confiscated from confederate soldiers were set aside to be distributed among Black families. This was the first systematic attempt at reparations for Black people, but it didn't last long. Less than a year after the Order was passed, it was reversed. The land went back to its former Confederate owners, under who it remains to this date. Land ownership remains tenuous for Black and Indigenous farmers today.

WATCH: Food justice: a vision deeper than the problem | Anim Steel | TEDxManhattan

Contemporary land struggles

Despite this history, by 1920, the United States had about 1 million Black farmers; however as of the 2017 Census of Agriculture, this number is closer to 45,000, and just 0.52% of the total farmland in the country is owned or operated by a Black farmer. How did this happen?

Over the last century, Black farmers were dispossessed of 12 million acres of land. A significant portion of this—6 million acres—occurred between 1950 to 1969, and according to writer Vann R. Newkirk II, can be tied with the rise of the civil rights movement. Additionally, federal programs during that time were designed to create larger, more consolidated farms (more on this later!) that drove many small and medium scale farmers off their land. Black farmers, and especially those that were in the South, were particularly vulnerable due to the systemic racism that persisted in federal agencies that were charged with providing credit, capital, and insurance to farmers that would help them remain on their land. Aside from this, legal loopholes like ‘Heir’s property’ prevented and continue to impede Black people from using their land to get loans or available federal disaster relief, and maintain control over its sale.

WATCH: The Great Land Robbery: How Federal Policies Dispossessed Black Americans of Millions of Acres

Indigenous producers and communities face different challenges when it comes to land. In 1848, the Dawes Act, or the Allotment act forced indigenous people into a system of private property ownership that did not exist in their traditional land tenure systems and enabled the sale of ‘surplus’ land to non-Natives. After being dispossessed from land that their ancestors stewarded for centuries, many indigenous communities are still fighting for sovereignty over their land and its resources. Forcing indigenous people to assume a capitalist, proprietary relationship with the land has not only threatened their sovereignty over the land but fractured their spiritual connection with the land—a vital component of indigenous culture.

A report on the mass incarceration of people of Japanese ancestry following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 found that the decision to intern more than 110,000 people was partly initiated by West Coast farmers’ racist resentment of Japanese farmers. During that time, Japanese-American farmers produced more than 40 percent of California's commercial vegetable crop alone and generated a much higher income per acre than white farmers. West Coast farmers who were threatened saw the war as an opportunity to rid themselves of the competition, and also gain access to some of the most fertile farmland in the region. About 258,000 acres of land was ‘confiscated’ from Japanese farmers and was never fully returned to them; and the impact of their dislocation has had a generational effect.

READ: The dangerous economics of racial resentment during World War II

Reevaluating our relationship with the land

Starting with indigenous ancestors that fought back against relocation and the group of Black leaders in Savannah, GA who advocated that ‘40 acres and a mule’ be given to previously enslaved families, to organizations like the National Black Food and Justice Alliance (NBFJA), Southeastern African American Farmers’ Organic Network (SAAFON), the Land Loss Prevention Project, Northeast Farmers of Color Land Trust, White Earth Nation and BIPOC producers who are growing food and advocating for themselves across the country, the desire to maintain relationship to the land among BIPOC communities is as old as the attempts to deny them land access and sovereignty.

While these organizations lead the fight to ensure land access for existing BIPOC producers, those like New Communities Land Trust are providing spaces where people from BIPOC communities can reconnect with land and farming. In urban areas, where communities are burdened by the twin forces of gentrification and food apartheid, community gardens stewarded serve not only as a source of food but as a community meeting space and sanctuaries.

As European settlers colonized North America, they also exposed vast expanses of land to the plow for the first time and it only took a few decades until their mode of farming drove around 50 percent of the original organic matter from the soil into the sky as carbon dioxide. Much of the work being done by traditional farmers and new proponents of regenerative agriculture is geared towards undoing this colonial legacy and restoring land to its earlier, more fertile state. Together, the work of these organizations plays a crucial role in redefining our collective relationship with the land, nurturing food sovereignty, mitigating food apartheid, and healing the planet.

Despite being denied access to land and resources, and historically left out of policy decisions, BIPOC communities retain a deep connection to land and agriculture. For many BIPOC communities, working together has been critical to surviving systems that were designed to work against them. For BIPOC producers, finding alternatives to private land ownership, as well as utilizing traditional agricultural practices that rely on ecological knowledge has been crucial to surviving a capitalist food system. Indigenous practices, BIPOC led food sovereignty, climate justice, and civil rights movements also spearheaded practices that are essential to contemporary food movements such as regenerative agriculture, cooperative ownership, and community-stewardship of land and water. However, increasing consolidation in the food and farming industry and a host of other barriers including a race-based wealth gap, institutional discrimination, and lack of market access has made it increasingly difficult for BIPOC farmers and fishers to continue these practices.

If the legacy of US agriculture is colonization and enslavement, it’s contemporary realities are rooted in capitalism. The current political and legal infrastructure of the food and farming sector is skewed heavily in favor of large corporations, whose profits hinge on the exploitation of workers and extraction from the land and oceans, and manipulation of democratic decision-making processes. As a result, the farming and fishing sectors are becoming increasingly consolidated. The majority of food production comes from farms that are larger than 2000 acres, and the largest 4 percent of farms make up 60% of all farmland.

From the Green Revolution of the late 1950s, the “Go big or get out” policies brought in by USDA Secretary Earl Butz in the 1970s large-scale farms, to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the nineties, government intervention in the agricultural sector has served the purposes of agribusiness, and not small and medium-scale farmers. In the past decades, large operations were able to leverage their scale to take advantage of technology, globalization, and a lack of antitrust enforcement to consolidate operations and push small farmers out.

A 2019 article from Time magazine captures the grim reality facing small farmers across the country: an unprecedented number of farm closures (100,000 farms closed between 2011 and 2018), farm debt at an all-time high of $418 billion, and declining mental health. At the same time our ocean commons - much like with land - is transforming into a private property asset, displacing community-based fishers and undermining conservation goals. In July 2020, the first batch of Genetically Modified Salmon produced by a biotechnology company entered the market despite warnings from conservationists, climate justice groups, and indigenous communities.

READ: A reflection on the lasting legacy of 1970s USDA Secretary Earl Butz

WATCH: Salmon People: The Risks of Genetically Engineered Fish for the Pacific Northwest

Before Black Indigenous, and other People of Color even had the right to vote in this country, the government was writing rules to favor industrial agricultural production practices. The first US Farm Bill, written in the 1930’s, calcified subsidies to increase production on monoculture farm operations - mostly dependent on chemical fertilizer inputs. Agent Orange, chemical warfare leftover from World War II, was put to use as a pesticide on farms, commonly known as DDT. Over the years, with technological and chemical investments controlled by corporations came the push to Get Big or Get Out of farming.

Today, the food and agriculture industry spends billions of dollars lobbying each year, and their influence over policy means that the rules are still largely written in their favor. We’re now left with a reality of larger farms but fewer farmers and recent political decisions like the trade war on China have pushed many remaining small farmers, and rural economies over the edge. Under this system, where large corporations control almost every aspect of farming, it is often unviable to go against the current, irrespective of who you are—even without the additional barrier of structural racism.

Most farmers now rely on government bailouts and crop insurance to offset their losses and keep themselves afloat through particularly difficult seasons, but government aid has not reached all farmers equally. The payments are based on production: the bigger the farm, the bigger the payments and loans are configured to serve large scale farmers. According to a report by NPR, about 100,000 individuals collected 70% of the money. BIPOC farmers, on the other hand, have historically been left out of USDA programs including disaster relief, conservation grants, and loan assistance due to discriminatory lending practices and inadequate outreach and assistance to their communities.

Rather than rewarding farmers who practice ecological agricultural techniques that have long lasting positive effects on soil health, and air and water quality, such programs continue to benefit megafarms that practice extractive agriculture that contributes to the climate crisis. As a result, small farms engaged in ecological agricultural practices, struggle to remain viable in a market-based economy.

For BIPOC producers, though many of them have ancestral connections to agriculture and come from communities that have stewarded land for generations, continuing those traditions as a vocational farmer is impossible for a majority. Unlike their white counterparts they are also less likely to own land and have access to intergenerational wealth that can cushion their losses.

Yet, as you’ll see in the following sections, there is a growing number of BIPOC farmers that are at the forefront of the agroecological movement.

Resources

- Native land CA map – Native Land Digital

- The Invasion of America Interactive Map - Claudio Saunt, University of Georgia

- Reparations Map - North East Farmers of Color and Allies

- Leveling the Fields: Opportunities for Black People, Indigenous People, and Other People of Color – Union of Concerned Scientists & HEAL Food Alliance

- Diné Food Sovereignty - A Report on the Navajo Nation Food System and the Case to Rebuild a Self-Sufficient Food System for the Diné People

- Growing Economies Policy Brief - Union of Concerned Scientists

- A Guide to Tribal Community Co-operative Development - Minnesota Indigenous Business Alliance

- 50 State Food System Scorecard - Union of Concerned Scientists

- Black Lands Matter: The Movement to Transform Heirs’ Property Laws – The Nation

- Ten Ways To Save Your Land - Land Loss Prevention Project

- Land Loss Trends Among Socially Disadvantaged Farmers and Ranchers in the Black Belt Region - Federation of Southern Cooperatives/ Land Assistance Fund

- The dangerous economics of racial resentment during World War II – Quartz

- The Invasion of America – Aeon

- The Great Land Robbery – The Atlantic

- HEAL Webinar - Sowing the Seeds of Liberation – HEAL Food Alliance

- Remaking the Economy in Indian Country – Nonprofit Quarterly

- With these Hands – SAAFON

- Thriving Communities Gathering – Thriving Communities

- Farming While Black – Kontent Films ‘

- American Indian Homelands: Matters of Truth, Honor and Dignity Immemorial’

- Food justice: a vision deeper than the problem – Anim Steel | TEDxManhattan

- The Great Land Robbery: How Federal Policies Dispossessed Black Americans of Millions of Acres – eHistory

- Local Bites Podcast

- The New American Farmer: Immigration, Race, and the Struggle for Sustainability - Laura-Anne Minkoff-Zern

- Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression - Robin D. G. Kelley

- Homecoming: The Story of African-American Farmers - Charlene Gilbert

- Working the Roots: Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing - Michele Elizabeth Lee

- Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement (Justice, Power, and Politics) - Monica M. White

- Black, White, and Green: Farmers Markets, Race, and the Green Economy - Alison Hope Alkon