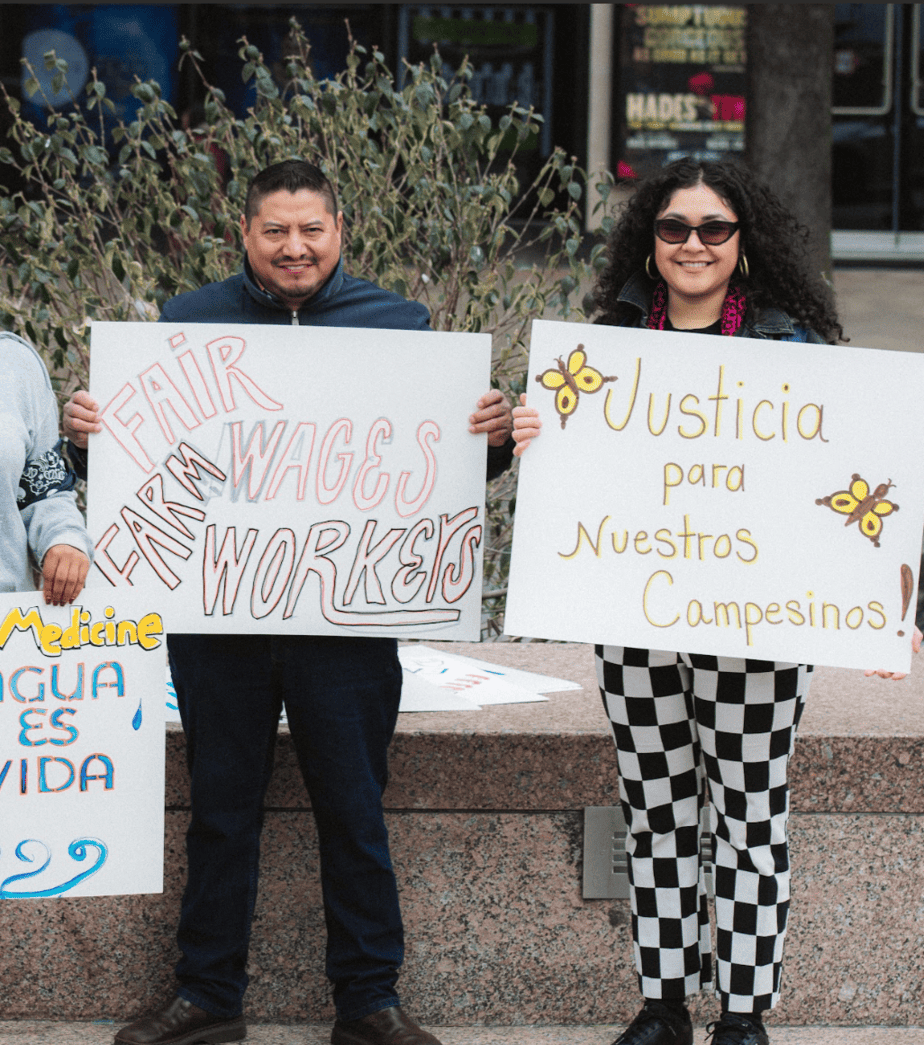

The 21.5 million people who work in our food system are integral to every aspect of food and farm policy. However, they are currently excluded from farm bill provisions and programs.

Much of US agricultural policy depends on a distinction between owners and workers. This distinction goes back hundreds of years, and is rooted in our economy’s reliance on slavery: unpaid labor to work the fields. This system enabled white landowners, businesses, and industries to reap huge profits by not compensating enslaved Black farmworkers and treating them as disposable. When Congress wrote the farm bill and labor laws in the 1930s, they excluded the jobs that had historically been held by enslaved people, including farmworkers. Today, many large agribusiness corporations and food retailers continue to exploit and underpay the food and farm workers who keep us all fed. Powerful corporations are able to do this because our laws devalue some people’s lives and worth, based on intersections of race, nationality, age, gender, and other identities.